Colchester Branch 026 Heritage Room

Open Hours: Monday 9:30 – 11:00 AM

By appointment – Contact:

Bud MacDonald – 902-897-4809

Phillip Richardson – 902-890-7459

The Heritage Room forms an integral role in Colchester Branch 026. It constitutes a tremendous reminder of the contribution made by so many in all military conflicts involving Canadian men and women on the world stage.

Artifacts from all branches of services – Land, Sea and Air – are on display and readily available. The room’s contents provide a tremendous resource for the families of Veterans and the community in general. The prospects of its importance as an academic resource are largely untouched.

Bud MacDonald responded to a call to provide assistance about twelve years ago. The Wentworth native and Military Veteran (Air Force – Flight Engineer 1948 – 1972) takes pride in maintaining the room and its contents, and making it available to all who wish to benefit from it.

Phillip served with the Nova Scotia Highlanders C Company during the 1970’s. Even though he’s assuming greater responsibility in the Heritage Room, he still considers himself in training under Bud’s watchful eye.

November 2019 – The ITALIAN CAMPAIGN

The spring of 2020 will mark the 75th anniversary of the Italian Campaign. Canadian participation in this twenty month operation was heavy. So too, were the losses.

The spring of 2020 will mark the 75th anniversary of the Italian Campaign. Canadian participation in this twenty month operation was heavy. So too, were the losses.

Beginning in July, 1943, 93,000 Canadians, along with allies from Great Britain, France and the United States, pushed south to north, matched against Germany’s best troops and defensive lines. When it ended in 1945, there were 26,000 Canadian casualties (nearly 6000 killed)

The original objective was to divert German resources from the Eastern Front, to ease German pressure on the Soviet Union. It worked.

Sicily, an island south of Italy, became the starting point. On 10 July 1943, Canadian troops with Operation Husky came ashore in what was one of the largest seaborne operations in military history, involving nearly 3000 allied ships. In four weeks Sicily was under allied control.

This was an important victory, clearing the way for landing in Italy. The coup deposing Italian Dictator, Benito Mussolini, caused the surrender of Italy; however, the German forces were not prepared to lose Italy.

On 3 September 1943, the allies came ashore and the fierce street fighting was underway. The Battle of ORTONA saw Canadian troops heavily involved in the liberation of that town. That victorious Liberation was successfully completed 28 December 1943.

The allies made their way north and by late summer and fall of 1944, broke through Germany’s Gothic line. Fighting continued into the spring of 1945 when, finally, the Germans surrendered (2 May 1945).

Canadians, however, did not participate in that final victory. By February 1945, they were transported to North Eastern Europe, joining the advance into the Netherlands and Germany enroute to the ultimate victory over Germany and the end of World War II.

Nova Scotia had proud representation in the landings at Sicily and Italy. The West Nova Scotia Regiment, mobilized in September 1939, fought in the Italian Campaign through to its transfer to the European Campaign.

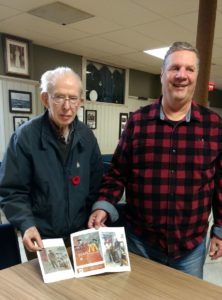

Pictured are Heritage Room Curators, Bud MacDonald and Phil Richardson displaying a pamphlet for the War Museum at CASTEL di Sangro, Italy. Branch 26 was instrumental in providing the Museum the West Nova Scotia Regimental Battledress. That Regiment played a pivotal role in the battle to liberate the community from German hands in November 1943.

September 2019 – BATTLE OF HONG KONG

In 1842, Hong Kong became a Colony of the British Empire. A new arrangement in 1898 saw Britain obtain a 99-year lease from China. In 1997, sovereignty of the colony was restored to China. Much happened over those years.

In 1842, Hong Kong became a Colony of the British Empire. A new arrangement in 1898 saw Britain obtain a 99-year lease from China. In 1997, sovereignty of the colony was restored to China. Much happened over those years.

Contrary to what many think, Canada’s first military engagement in World War II was not in Europe, rather, in Hong Kong. Thought of Japanese attack appeared likely. In 1941, upon request of Britain, Canada sent two battalions – the Winnipeg Grenadiers and the Royal Rifles of Canada (Quebec) – to perform guard duty and display a show of force in the Territory of Hong Kong.

In October, 1941, the two battalions, numbering 1975, sailed from Vancouver, arriving in Hong Kong 16 November. They joined up with units from the United Kingdom, India, China and volunteers from the Territory.

On 7 December, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbour. Six hours later the attack on Hong Kong was underway. The Japanese were battle-hardened after fighting in China since 1937. The Canadians and their allies were quickly in a fight for their lives. While their efforts were valiant and the counter attacks effective, the outcome became obvious. On Christmas Day 1941, the allied forces surrendered to the Japanese.

As prisoners-of-war, for the next three and one-half years, they suffered beatings, hard labour and inadequate diet. Prison war camps were originally in Hong Kong but later moved to Japan. Of the 1975 Canadians, 290 were killed in action and another 264 died from inhumane treatment as prisoners-of-war.

In August, 1945, almost four years after the fall of Hong Kong, the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki forced the surrender of the Japanese and the end of war in the Pacific. The surrender was formally signed 2 September 1945, seventy-four years ago this month.

One thousand, four hundred, eighteen Canadians (1418) returned home.

Pictured, a plaque in Branch 026 Lounge commemorating those who fought in defense of Hong Kong during World War II. It was presented by Karen MacKay, daughter of Laurie MacKay, who was born and raised in Truro and was a member of the Royal Rifles of Canada (Quebec City), one of two Canadian contingents sent at the request of Great Britain.

July 2019 – BATTLE OF NORMANDY

June 6, 1944 will be forever known as D-Day. On that day, 150,000 Canadian, American, and British Soldiers landed on five beaches along the 50-mile stretch of heavily fortified coastline of France’s Normandy coast.

June 6, 1944 will be forever known as D-Day. On that day, 150,000 Canadian, American, and British Soldiers landed on five beaches along the 50-mile stretch of heavily fortified coastline of France’s Normandy coast.

The invasion, code-named Operation Overlord, was to begin the liberation of Western Europe from Nazi occupation. It was anticipated, coming with great human loss.

Canada’s involvement on that day was substantial: 14,000 soldiers and paratroopers, supported by the Royal Canadian Navy (110 ships, 10,000 sailors) and the Royal Canadian Air Force (15 fighter and fighter-bomber squadrons). At the end of the day there were 1074 Canadian casualties, including 359 killed.

That day marked the beginning of the Battle of Normandy which would continue through to the encirclement of the German Army in FALAISE on 21 August. None of the attacking Allied Forces met D-Day objectives; however, the Normandy beachhead was secured, enabling waves of allied troops, tanks, artillery and supplies to come ashore.

Planning for the invasion began the previous year. The Battle of the Atlantic was largely won; the Allies gained a foothold in Europe with success in Italy; and Soviet forces were rolling back the German War Machine on the Eastern front. The Germans knew an attack was inevitable but they didn’t know when or where. Their best bet was at Pas de Calais, the shortest distance from England. As it turned out, secrecy and surprise were the Allies’ greatest weapons.

When the Canadians hit Juno Beach, they learned quickly the Atlantic Wall was formidable. The concrete bunkers, machine gun nests, layers of barbed wire, mines and anti-tank trenches were on full display. Advancement was slow.

On 4 July, the Canadian and Polish soldiers led the assault on CARPIQUET airport on the outskirts of CAEN. Despite fierce opposition, success was gained. By early August, the Allied Armies moved south toward FALAISE while the Americans completed the encirclement preventing German retreats through FALAISE GAP. On 21 August, 150,000 Germans were captured, ending the Battle of Normandy.

Over that three-month period, the Allies suffered 209,000 casualties, including more than 18,700 Canadians (over 5,000 Canadians killed). As was the case during World War II, the end of one battle was the beginning of the next. The Allies turned their attention to pursue the enemy in the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany. Within a year, it would be all over.

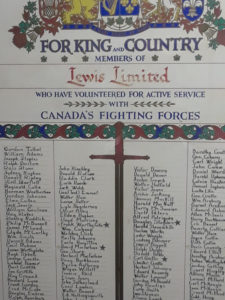

As you enter the Heritage Room, you may notice a large framed scroll displaying names of the employees of the Lewis Hat factory who volunteered for active service in World War II. Many were involved in the D-Day invasion, June 6, 1944.

The Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) have developed a reputation for their strong response when called upon, at home and abroad. Their history is deep and rich.

OPERATION LENTUS is the CAF response to natural disasters. Hurricanes, floods and forest fires are common to certain regions and seasons in Canada, and they seem to occur more frequently as the years go by. While Provincial and Territorial authorities are first to respond, they may seek the help of the CAF and Operation LENTUS, if overwhelmed.

Operation LENTUS has an established plan of action, adaptable to multiple situations: help Provincial and Territorial Authorities; respond quickly and efficiently to the crisis; and, stabilize the natural disaster situation.

Last year (2018), the CAF responded to winter storms in Quebec, forest fires in British Columbia and floods in British Columbia, New Brunswick and Ontario.

On April 19, 2019, Provincial authorities in New Brunswick and Quebec requested federal assistance with flood relief. The Ministers of Public Safety and National Defence committed support from the CAF. On April 20, the CAF deployed immediate response units to the affected areas. Operation LENTUS was underway.

Their tasks included: filling and moving sandbags; providing assistance to the most vulnerable; conducting wellness checks; assisting with evacuations; and, supporting efforts to protect property. The number of people to be sent and the assets deployed are based on the scale of the natural disaster.

The sight of hundreds of Canadian Armed Forces personnel was a welcomed one in the flood-stricken areas of New Brunswick and Quebec last month. This is what community members should do to assist each other.

Since its start in January 1942, Germany’s strategic submarine offensive against North America’s eastern seaboard had claimed 48 victories in Canada’s east coast waters. A new phase surfaced as the offensive moved inland to Canada’s heartland.

On 11 May 1942, a British freighter carrying war supplies out of Montreal was torpedoed off the west coast of Gaspe Peninsula. The same night a Dutch freighter suffered the same fate. These developments led to the creation of the “Gulf Escort Force” consisting of Corvettes, Minesweepers and Motor Launches to escort convoys coming from Quebec through to the Atlantic. The 117 Squadron of the Royal Canadian Air Force out of Mont Joli and North Sydney provided additional anti-submarine support.

During the remainder of the 1942 ice-free season, the Escort Force and air counterparts continued its fight against the deadly German submarines. The last loss of that 1942 season was the largest, the sinking of the Sydney to Port Aux Basques ferry, the Cariboo, on 14 October. Of the 237 crew and passengers, only 101 survived. Included among the dead were crew members, civilians, British, American and Canadian military personnel.

More than any other event, this loss revealed to Canadians how vulnerable they were to sea attacks, and that World War ll was not just a European event. Between 1942 and November 1944, German U-boats sank 23 ships, including four Canadian Warships in the St. Lawrence and the Gulf. Despite these losses, the Battle marked a strategic victory for Canadian forces, disrupting U-boat activity and protecting Canadian and Allied convoys.

In May 1945, following Germany’s surrender, U-boats 889 and 190 surrendered to the Royal Canadian Navy at Shelburne NS and Bay Bulls NL. So ended the Battle of the Gulf of St Lawrence.

One of the ships deployed during that Battle was the HMCS TRURO. This was a Bangor Class Minesweeper, built in Quebec and launched 5 June 1942. With a maximum speed of 16.5 knots (30.6 km/h) and a crew of six officers and 77 crew, it proudly supported the Gulf Escort Force.

In March 2010, the ship’s namesake, Truro NS, was presented a permanent reminder of the town’s connection with the Navy, with an inscribed framed photograph of the HMCS Truro and its history to commemorate the Navy’s Centennial Anniversary. This can be seen in Truro’s Town Office.

Ships named after communities were often adopted and a special relationship developed between the sailors and residents of the namesake. Truro Junior High School had a long standing tradition with the HMSC Truro. The school’s foyer displays ship artifacts, including a life preserver and the ship’s original flag.

JANUARY 2019 – LIBERATION of NETHERLANDS

When you walk into the Heritage Room, look straight ahead, you can’t miss it. That colourful flag, pictured above, is in recognition of the Fiftieth Anniversary of the liberation of the Netherlands. The Seventy-fifth is coming up in 2020.

When you walk into the Heritage Room, look straight ahead, you can’t miss it. That colourful flag, pictured above, is in recognition of the Fiftieth Anniversary of the liberation of the Netherlands. The Seventy-fifth is coming up in 2020.

The German invasion of the Netherlands began 10 May, 1940. The neutral country was no match for the military might of the Nazi war machine. The bombing of Rotterdam on 14 May resulted in the surrender to the German invaders.

So began years of hardship. Persecution of the Jewish population was followed by heavy restriction on everyday life, escalating with time and best described as horrible conditions. Forced compliance to Nazi ideology was firmly underway.

In the final months of World War II, Canadian forces were given the important task of liberating the Netherlands from German occupation. Since the Battle of Normandy in the summer of 1944, the First Canadian Army was Canada’s fighting force in northwest Europe. Upon reaching the Netherlands, this strike force, under Canadian leadership and containing contingents of British, Polish, Americans and Dutch infantry and armoured troops, was on a mission to clear the enemy from the multi-chanelled Scheldt River.

The fighting through October 1944 was fierce. By 8 November, the estuary and islands were secured. By 28 November, the first cargo of Allied cargo entered the port of ANTWERP (Belgium), destined for the Netherlands. The Battle of Scheldt was costly.

The First Canadian Army spent the winter patrolling its portion of the front line in the Netherlands and France. In February 1945, the offensive to drive the Germans across the Rhine River was underway. By late March, the Canadians began rooting out German forces in large portions of the Netherlands.

The Canadians were greeted as heroes as they liberated small towns and major cities. Canadian troops facilitated the arrival of food, fuel and basic supplies to a population in the midst of starvation.

General Charles Foulkes, commander of the 1st Canadian Corps, accepted the surrender of German forces in the Netherlands on 5 May. Two days later, Germany formally surrendered and the War in Europe was over.

More than 7,600 Canadian soldiers, sailors and airmen died fighting in the Netherlands. Canadians were recognized as both liberators and saviors. So began a long-lasting bond of friendship between the two countries.

We will remember them

NOVEMBER 2018 – ARMISTICE DAY

Ar

Ar mistice Day marked the end of hostilities during the First World War, acknowledging victory for the Allied Forces and a complete defeat for Germany. This agreement to stop fighting was signed by France, Great Britain and Germany on the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month, 1918. That is when the fighting was to end even though it was agreed upon six hours earlier.

mistice Day marked the end of hostilities during the First World War, acknowledging victory for the Allied Forces and a complete defeat for Germany. This agreement to stop fighting was signed by France, Great Britain and Germany on the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month, 1918. That is when the fighting was to end even though it was agreed upon six hours earlier.

The inaugural Armistice Day in Canada was in 1919, on the second Monday in November. In 1921, the Canadian Government moved to observe ceremonies on the first Monday in the week of November 11, combined with Thanksgiving Day. That created problems.

At the founding convention of the Royal Canadian Legion in Winnipeg, 1925, a resolution to observe Armistice Day only on November 11 was passed. On March 18, 1931, the Canadian Government agreed to observe it on November 11, and “no other day”. The name was changed to Remembrance Day to reflect remembrance of war dead from all military conflicts involving Canada. Thanksgiving Day was moved to October.

Services varied in size and significance from year to year; however in 1995, the 50th Anniversary of the end of World War II, there seemed to be a major upsurge in attendance throughout the country. Each time Canada was called upon to defend peace and freedom, Remembrance Day drew larger ceremonies in communities large and small.

The cost of Canada’s involvement in World War I was high. Close to 61,000 Canadians were killed and another 172,000 wounded. Newfoundland, a colony of Great Britain, recorded 1,305 deaths and several thousand wounded. With a Canadian population of less than 8,000,000 at that time, it was remarkable that more than 650,000 served in uniform.

Canada earned newfound respect and recognition – home and abroad – that it was an independent country in its own respect. The Treaty of Versailles was signed June 28, 1919, to officially end the state of war between the Allied Powers and Germany. It was only fitting that Canada earned a separate signature on that treaty.

The Truro Cenotaph was dedicated September 26, 1929 in memory of the men who during The Great War (1914-1918) nobly upheld the honour of the empire in France and Flanders. Names of others killed in conflict have been added. It is a scene which swells emotion in November of each year.

Pictured, as well, is a Red Ensign proudly displayed in the Branch Heritage Room. Private William Coulter, a Truro native, while in France, somehow obtained it and sent it home to his mother, Mary. He was killed in action April 29, 1916, buried in Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery, Belgium. He was 18.

We Will Remember Them

September 2018 – 100 Day Offensive

The final push through Belgium and France which ultimately brought WWI to an end has been referred to, by Canadians, and others, as Canada’s Hundred Days – and for good reason.

The final push through Belgium and France which ultimately brought WWI to an end has been referred to, by Canadians, and others, as Canada’s Hundred Days – and for good reason.

After the outbreak of the War, the fighting in those countries quickly turned into a stalemate of trench fighting, with the Allied and Germans facing one another across a “No Man’s Land” of barbed wire, shell craters and mud. This Western Front stretched from the North Sea to the Swiss border. Devising effective tactics to deal with these realities was a struggle. “Over the Top” was the attack of choice, resulting in great human loss with little territorial gain.

In March of 1918, the German forces operated a Spring Offensive along the Front, feeling this could be their real last chance to defeat the Allied Forces. With Russia withdrawn from the War, and the full resources of American deployment not yet applied, this was their opportunity. Gains were made but not of any crucial Allied positions.

The Allied Counter Offensive kicked off on 8 August, and so began the final one hundred days. After Vimy (April 1917), Canada gained a reputation for being the best attacking Allied Troops. The Canadian Corps took the lead in the Battle of Amiens (8 August – 12 August), advancing 20 km in three days. This surprise attack was a breakthrough, referred to by German forces as “the black day of the German army”.

The Canadian Corps moved on to Arras, given the task of cracking the Hindenberg Line, the Germans’ main defensive line along the Western Front. Penetration of the Drocourt-Queant line on 2 September was the beginning of the end.

Under cover of the heaviest single day bombardment of the entire war (27 September) at Canal du Nord, the Canadian corps broke through 3 lines of German defence. After further heavy resistance, the Canadians saw their last action as a whole corps.

Individual Divisions continued to fight to the very end, with the War’s last Canadian combat death – Private George Prince – killed two minutes before the fighting officially ended 11 November. Over those 100 days, the Canadian corps, in its lead role, advanced 130 km, capturing 32,000 prisoners. The cost was heavy – more than 6,800 Canadians and Newfoundlanders were killed with another 39,000 wounded.

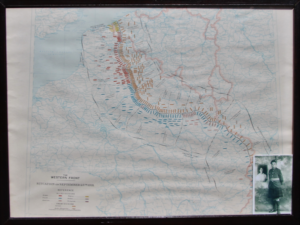

Before entering the Heritage Room, check out the Map of the Western Front dated 25 September, 1918. Pictured on the bottom of the map (above) is a photo of Pte Sydney Hale (85th Battalion), killed 2 September, 1918 on the Drocourt – Queant line.

July 2018 – HMCS Athabaskan

When speaking about HMCS Athabaskan, you have to be specific – there were three of them.

When speaking about HMCS Athabaskan, you have to be specific – there were three of them.

The original, commissioned in February 1943, was British built. Missions included the Arctic Blockade (off Iceland), submarine patrols and convoy escort in the English Channel. She was torpedoed and sunk in the English Channel in April 1944. Her captain and 127 men were lost, 85 were taken prisoner, 42 were rescued by sister ship, HMCS Haida, and 6 reached England in a small craft.

The second version, also a Tribal-Class Destroyer, was built in Halifax, launched May 1946 and commissioned January 1948. She served as a training ship in the Pacific until the outbreak of the Korean War in which she served three tours of duty. She later served in the Second Canadian Escort Squadron (Pacific Command). In 1969, she was sold for scrapping after decommissioning in 1966.

The third Athabaskan was built at the Davie Shipyard (QC), launched November 1970 and commissioned September 1972. This Iroquois-class destroyer was a class of four helicopter-carrying, guided missile destroyers of the Royal Canadian Navy, serving from 1972 to 2017. The Cold War Era ship served NATO missions in the Atlantic as part of the Standing Naval Force Atlantic, participated in the Iraq-Kuwait War in the Persian Gulf as Flagship of the Canadian Naval Task Group (1990-1991), provided disaster relief in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina (2005), was deployed for disaster relief following the Haiti earthquake (2010) and continued NATO naval exercises until decommissioned. The ship’s final Sail Past in the home port of Halifax was in March 2017. The Athabaskan was sold for dismantling by Marine Recycling at their facility in Sydney (Summer 2018).

Pictured is Branch 26 Second Vice-President, Ed Simpson, who served aboard the Athabaskan in the late 1970s. He is holding a shell casing from the ship and the ship’s Coat-of-Arms which was presented to the Heritage Room by Branch Sergeant-at-Arms and former Athabaskan crew member, Terry Farrell.

May 2018 – Helping Hand

If seeking military information, the Branch 26 Heritage Room is a good place to start.

If seeking military information, the Branch 26 Heritage Room is a good place to start.

Such was the case for Oscar Harris who became a member of Branch 26 in April of this year. He came to the Heritage Room looking for some help and direction, as well as having in his possession a wealth of family military history which can be traced back to the Battle of Little Bighorn (1876). Of particular interest was his uncle, Lewis Harris, who was killed in action in the second Battle of Arras on August 26, 1918.

Lewis Harris was a native of Little River Harbour, District of Argyle, Yarmouth County. He enlisted on December 27, 1916 in Halifax and became a member of the Canadian Medical Corps. Upon his arrival in France, he was transferred to the 3rd Battalion Canadian Machine Gun Corps. Pictured is Lewis Harris, his Mother’s Memorial (Silver) Cross, as well as supporting documentation.

Oscar Harris has been consolidating the family’s information but has been unable to locate two service medals, or even to determine whether they were ever received by the family. Of interest are the British War Medal and the Victory Medal, both of which were to be awarded to his uncle. The British War Medal was awarded to Canadian Overseas Military forces who came from Canada between 5 August 1914 and 11 November 1918, or who had served in the theatre of wars. The Victory Medal was an Inter-Allied War Medal agreed upon in 1919 and was to be awarded to all ranks of the fighting forces. Oscar Harris is determined to have them as part of his collection.

He and his wife, Elaine, moved to Truro six years ago. His interest in his family’s military involvement brought him to Branch 26. He’s glad it did.

June 2017 – Battle of Normandy

On June 6, 1944, the Allies invaded Western Europe in the largest amphibious attack in history. The Battle of Normandy, which lasted from June to August resulted in the liberation of German-occupied regions and contributed to the Allied victory on the Western Front.

On June 6, 1944, the Allies invaded Western Europe in the largest amphibious attack in history. The Battle of Normandy, which lasted from June to August resulted in the liberation of German-occupied regions and contributed to the Allied victory on the Western Front.

At the end of that June 6 day, the Gold and Juno beachheads were linked, and by June 12, the other beachheads (Utah, OMAHA and SWORD) were connected bringing the 80 km stretch of Normandy coast under Allied control. The Allied foothold extended steadily over the ensuing months. Allied casualties were at least 10,000, with 4,414 confirmed dead.

The Amphibious landing was preceded by aerial and naval bombardment and an airborne assault (24,000 American, British and Canadian Airborne troops). Included was the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, created in July 1942 as a response strategy in the event of German attack on Canadian soil. As it turned out, this Battalion was the first Canadian unit on the ground on D-Day.

The elite unit landed behind enemy lines between 0100 – 0130 hours on June 6. Despite heavy German resistance, the Battalion achieved its three main objectives: destruction of a major bridge, securing the left bank of the 9th Parachute Battalion (British); and taking control of a major crossroad. Of the 27 officers and 516 men from the Battalion, 24 officers and 343 gave their lives.

Following the invasion, the Battalion was reorganized and retrained to regain its strength and combat readiness. It served in ground operations in the later days of the Battle of the Bulge, then on to the liberation of the Netherlands.

Pictured is the camouflage weather-protective tunic which belonged to Don McInnis, a Truro native and proud member of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion.

April 2017 – Vimy Ridge

Some say Canada came of age in the April days of 1917. It was the first time all four Divisions of the Canadian Expeditionary Force fought together as one formation. At heavy costs (7,700 killed and wounded), their task of taking Vimy Ridge was accomplished.

Some say Canada came of age in the April days of 1917. It was the first time all four Divisions of the Canadian Expeditionary Force fought together as one formation. At heavy costs (7,700 killed and wounded), their task of taking Vimy Ridge was accomplished.

The Canadians moved to the front line in August 1916. That winter was spent strengthening the lines, digging tunnels and underground bunkers, stockpiling supplies, all in preparation for the assault on Vimy.

At 5:30 am, April 9 (Easter Monday), the assault began. The 4th Division faced the toughest objective. It was to take Hill 145, a strategic German strong point. Assigned to that Division was the 85th Battalion, a distinctive Nova Scotia Highland Regiment.

The 85th, raised in 1915, was a working unit, on call. They did the grunt work — maintaining dumps, cleaning and repairing trenches, carrying ammunition and mopping up, while remaining battle ready.

By late afternoon on April 9th, the 4th Division was in trouble. The advancing Battalions were pinned down in the mud below Hill 145. The only fresh, available support was the 85th.

At 6:00 pm, two companies of the 85th came out of their trenches, with bayonets fixed. Once into the enemy trenches, the fighting was over in ten minutes. Hill 145 was in Canadian hands.

The “ugly duckling Battalion” made up of miners, farmers, fishermen and foresters from northern Nova Scotia earned a new label. They became the “Never Fails”. The 85th continued to distinguish itself through to the final One Hundred Days of WWI.

The mannequin is clothed in an 85th Battalion Officer’s Uniform. Comrade Wilson MacDonald’s grandfather, Henry P. MacDonald (Springhill), was a member of the 85th. Many in this area share a very similar attachment to this Battalion and its proud contribution to the war effort.

February 2017 – The Knobkierie

Pictured is an artifact that can be traced back to the Boer War (1899 – 1902). This was Canada’s first foreign war. Also known as the South African War, it was fought between Britain (with help from its colonies and Dominions such as Canada) and the Afrikaner republics of TRANSVAAL and the Orange Free State. Two hundred and seventy (270) Canadians were killed in the South African War in which Canadian troops distinguished themselves in battle overseas.

Pictured is an artifact that can be traced back to the Boer War (1899 – 1902). This was Canada’s first foreign war. Also known as the South African War, it was fought between Britain (with help from its colonies and Dominions such as Canada) and the Afrikaner republics of TRANSVAAL and the Orange Free State. Two hundred and seventy (270) Canadians were killed in the South African War in which Canadian troops distinguished themselves in battle overseas.

The walking stick was carved by Afrikaner Prisoner of War, P.J. Vanvuuren, while in P.O.W. Camp in Bermuda in 1902. With imagination and a piece of glass he carved the head of a dog (or maybe a baboon) holding a snake which coiled around the walking stick. The KNOBKIERIE was commonly used in South Africa for killing snakes or throwing at animals.

This artifact was retrieved by Pte. Alexander McCabe and donated to the Heritage Room by Helen Taylor in 2009. You just never know what you can find in that room.

December 2016 – Princess Mary Gift Box

Bud MacDonald and Phillip Richardson are shown admiring an embossed brass box, a World War Ⅰ artifact with the date, 1914, clearly displayed. This is a perfectly preserved Princess Mary Gift Box.

Bud MacDonald and Phillip Richardson are shown admiring an embossed brass box, a World War Ⅰ artifact with the date, 1914, clearly displayed. This is a perfectly preserved Princess Mary Gift Box.

Princess Mary, the 17-year-old daughter of King George Ⅴ and Queen Mary, generated a fund in November, 1914, to provide a Christmas gift for every sailor afloat and soldier at the front, wearing the King’s uniform and serving overseas. This token of love and sympathy was to be ready for Christmas, 1914.

The box (5”x3 ¼”x1 ¼”), with a hinged lid, provide something useful and permanent. For the smokers, the box contained a pipe, an ounce of tobacco, twenty cigarettes, a tinder lighter, a Christmas card and picture of Princess Mary. Non-smokers received a packet of acid tablets, a khaki writing case with paper and pencil, along with card and photo. Nurses received a tin of  chocolate candy, while Gurkhas, Sikhs and Indian troops received sugar candy and relevant spices.

chocolate candy, while Gurkhas, Sikhs and Indian troops received sugar candy and relevant spices.

Eventually, the gift went to all serving at home or abroad, prisoners of war and next of kin of 1914 casualties. The fund continued beyond Armistice in 1918, by then, 2.6 million had been distributed. It’s been noted that many of the recipients repacked the gift and sent them home to loved ones.

The Princess Mary Gift Box in Branch 26 Heritage Room was donated by Ruth Kent in 2007. This box contains a “bullet pencil” and card.

October 2016 – 193rd Battalion Nominal Roll

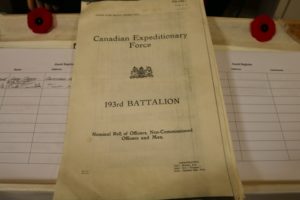

Pictured at left, Bud MacDonald holds the Nominal Roll of Officers, Non-commissioned Officers and Men of the 193rd Battalion, Canadian Expeditionary Force. The Battalion embarked from Halifax one hundred years ago (October 12, 1916) aboard the SS Olympic, en-route to England.

Pictured at left, Bud MacDonald holds the Nominal Roll of Officers, Non-commissioned Officers and Men of the 193rd Battalion, Canadian Expeditionary Force. The Battalion embarked from Halifax one hundred years ago (October 12, 1916) aboard the SS Olympic, en-route to England.

The members of the Battalion were recruited throughout the northern counties of Nova Scotia (Pictou, Colchester,Cumberland, Hants, Antigonish, Guysbourough). They trained as detachments in their home county, with Truro as Head Quarters, until 1916 when they mobilized with the four Battalions of the Highland Brigade in Aldershot.

Upon arrival in England (December 1916) the Battalion was dispersed to other units – 185th Cape Breton Highlanders, 25th, 85th, 58th and 17th Reserve Battalion.

Originally a non-combat Battalion organized in 1916, the recruits were destined to provide reinforcements to the Canadian Corps in the Field. The members of this Battalion, sometimes referred to as the “Cumberland Highlanders” eventually saw action throughout France.

A large number of Branch 026 Comrades can see the names of their Grandfathers who proudly stepped forward to serve.

August 2016 – No. 2 Construction Battalion

Pictured at left is Branch #26 President, Gerry Tucker, proudly holding a picture of the No. 2 Construction Battalion established one hundred years ago. The photo was placed in the Heritage Room by deceased comrade, John and Muriel Clyke.

Pictured at left is Branch #26 President, Gerry Tucker, proudly holding a picture of the No. 2 Construction Battalion established one hundred years ago. The photo was placed in the Heritage Room by deceased comrade, John and Muriel Clyke.

At the outbreak of World War I, the demand for recruits was huge, but enlistment by African Canadians was largely denied. Two years into the war, on July 5, 1916, an “all black” army construction battalion was created. The No. 2 Construction was granted at the Pictou Market Wharf, then moved to Truro.

The battalion was the first and only black unit ever established in Canada. All officers, with the exception of one, were white. The Chaplain, the Reverend Dr. William White, was black and a Truro pastor, one of the few black officers in the British Empire. The unit was clearly a segregated one with a non-combatant status. When it sailed to England (March 1917) it was 600 strong, half of that number being Nova Scotian and the remainder from the United States and the British West Indies.

In May 1917, the Battalion in France`s Jura Mountain region, joined four Canadian Forestry units charged with providing lumber for the War effort. The battalion returned to Canada in January 1919 and was disbanded in September 1920.

Each July since 1993, when a granite memorial in the Battalion`s honour was unveiled in Pictou, the Black Cultural Society of Nova Scotia conducts an annual service to commemorate their unique unit and the enduring place in Canadian Military History.

June 2016 – Kemptown United Church tablet

Pictured to left is Phillip Richardson holding a marble tablet removed from the Kemptown United Church. It holds the names of four community members who lost their lives in the service of their country during World War II. When repairs to the church and declining members led to the closure and eventual demolition of the church, Comrade Ernie Hingley, a native of that community, felt the tablet was too valuable not to be displayed. He felt the Heritage room would be a fitting home to this artifact where it would be available as a reminder of that community’s contribution to the War effort. His great grandfather, Alexander Scott Hingley, provided the original plate for the church. Most churches in this area have provided similar recognition of congregational members who have served.

Pictured to left is Phillip Richardson holding a marble tablet removed from the Kemptown United Church. It holds the names of four community members who lost their lives in the service of their country during World War II. When repairs to the church and declining members led to the closure and eventual demolition of the church, Comrade Ernie Hingley, a native of that community, felt the tablet was too valuable not to be displayed. He felt the Heritage room would be a fitting home to this artifact where it would be available as a reminder of that community’s contribution to the War effort. His great grandfather, Alexander Scott Hingley, provided the original plate for the church. Most churches in this area have provided similar recognition of congregational members who have served.

April 2016 – Books of Remembrance

Holding a very central position in the Heritage Room are two “Books of Remembrance”. These are the product of significant research started about fifteen years ago. It was Bud’s intention to catalogue the names of Truro and area residents who enlisted and were killed in the line of duty. Gathering the names was no easy task. Once a Service Number was obtained, the information was obtained from the World War II Book of Remembrance in Ottawa.

Holding a very central position in the Heritage Room are two “Books of Remembrance”. These are the product of significant research started about fifteen years ago. It was Bud’s intention to catalogue the names of Truro and area residents who enlisted and were killed in the line of duty. Gathering the names was no easy task. Once a Service Number was obtained, the information was obtained from the World War II Book of Remembrance in Ottawa.

An individual page is provided on each identified person with the Casualty Details including such information as Rank, Regiment, Date of Death and Cemetery. The page number where the information was obtained from the World War II Book of Remembrance is also noted.

At the back of each of these Books of Remembrance is information on the Cemeteries where these Canadians were buried. These books could serve as a great starting point for research. Documentation of this type grows in importance as the years move on.